Ersin Uskun1, Ayşe Çelik 1, Pınar Ersoy 1, Mustafa Volkan Yürekli 1, Orhan Karakaş 1, Ayşenur Beyazıt 1,

Ahmet Nesimi Personoğlu 1, İlker Büyükyavuz2

1Süleyman Demirel University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Public Health, Isparta, Türkiye.

2Süleyman Demirel University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Isparta, Türkiye.

SUMMARY

Purpose: In our country, where consanguineous marriages are common, births start at an early age and continue until older ages, and antenatal care remains below the targeted level, these factors are listed as the main causes of congenital anomalies.

The aim of this study is to determine the prevalence of congenital anomalies in children under the age of five in a rural province in the Mediterranean region and to examine possible risk factors.

Material-Method: The sample size was calculated in the INSTAT program and 1440 children under the age of five, selected by the stratified sampling method, were reached in rural Isparta. Data were collected by face-to-face survey administered to the child’s relative and by physical examination of the child, and were evaluated using chi-square, t tests and logistic regression analysis in the SPSS package program.

Results: The frequency of congenital anomalies detected in the research group was 3.0% and the frequency of disability was 1.4%. The most common congenital anomaly is undescended testicle. Variables determined to be associated with congenital anomalies; The child is male (gender), the mother’s working status, the baby was told that there was a problem during the pregnancy checks, and there is a history of bruising after birth.

Conclusion: In this study, the anomaly frequencies and related factors determined only in rural areas were found to be compatible with the literature. Similar studies should be conducted in larger universes.

Key Words: Congenital anomaly, Rural, Isparta

Entrance

Congenital anomalies are a condition that ranks second among the causes of perinatal morbidity and mortality after premature births and causes the death of many children under the age of five in the world every year (1, 2). It is an important public health problem in terms of incidence, morbidity and mortality rates (3,4). Living in rural areas where health services cannot reach extreme points may create a disadvantage in the early diagnosis and treatment of congenital anomalies. For this reason, it is important to detect congenital anomalies in rural areas and conduct regional studies to reveal the regional characteristics and risk groups of congenital anomalies.

Aim

The aim of this study is to determine the frequency of congenital anomalies in the population of children under five years of age in a rural area of a province in the Mediterranean Region and to examine their relationship with some variables.

Material-Method

This cross-sectional study was carried out between February 2013 and February 2014 in a rural area of a province in the Mediterranean Region. The population of the research consisted of children under the age of five living in the rural areas of the province. According to the sample size calculated in the GraphPad InStat program, it was aimed to reach 1440 people (5,6). The places to reach the sample were determined by using stratified and simple random sampling methods. Data were collected through a survey using face-to-face interview with the child’s parent/relative. Each child was physically examined and the findings were recorded. The ICD-10 classification was used as the basis for the classification of Congenital Anomalies (7). The dependent variable of the research is; It was the presence of a congenital anomaly. Independent variables; the child’s age, gender, number of children, place of residence and birth, family structure, presence of consanguineous marriage between the child’s mother and father, education level and employment status of the mother and father, income level, pregnancy planning status, whether the mother’s health check was made during pregnancy. condition, any problems with the baby detected during the check-up, drug, cigarette or alcohol use during pregnancy, time, manner and place of birth, person assisting in the birth, history of difficult birth and bruising after birth. Data were evaluated in computer environment using descriptive statistics, chi-square and t tests. In multivariate analysis, independent predictors in predicting the outcome of anomaly were examined using logistic regression analysis, using the variables identified in univariate analyzes and maternal age reported as a risk in the literature. Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used for model fit. Cases with a Type-I error level below 5% were considered statistically significant.

Before the research, approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the relevant university and necessary permissions were obtained from the institutions.

This study was financially supported by the Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit of the relevant university (Project No: 2537-M-10).

Results

The distribution of the research group and children with congenital anomalies according to family characteristics is shown in Table 1. 86.6% (n=1247) of the research group had been residing in the same place for the last five years. Of those who migrated to their current location (n=193), 62.2% (n=120) migrated from another provincial center. 71.6% (n=1031) of the research group was a nuclear family. The income level of 63.1% (n=909) of the research group was medium, and the income-expense balance of 55.8% (n=803) was equal. 95.8% (n=1379) of the research group had social security. The parents of 11.7% (n=168) of the research group were relatives. The average age of the mothers of the children in the research group was 29.6±5.3 (youngest = 17, oldest = 53), and the average age of the fathers was 33.0±5.3 (youngest = 18, oldest = 64). 59.4% of the mothers of the research group (n=855); 41.0% (n=590) of their fathers were primary or secondary school graduates. 15.3% of mothers (n=220) and 95.5% of fathers (n=1376) were working in an income-generating job.

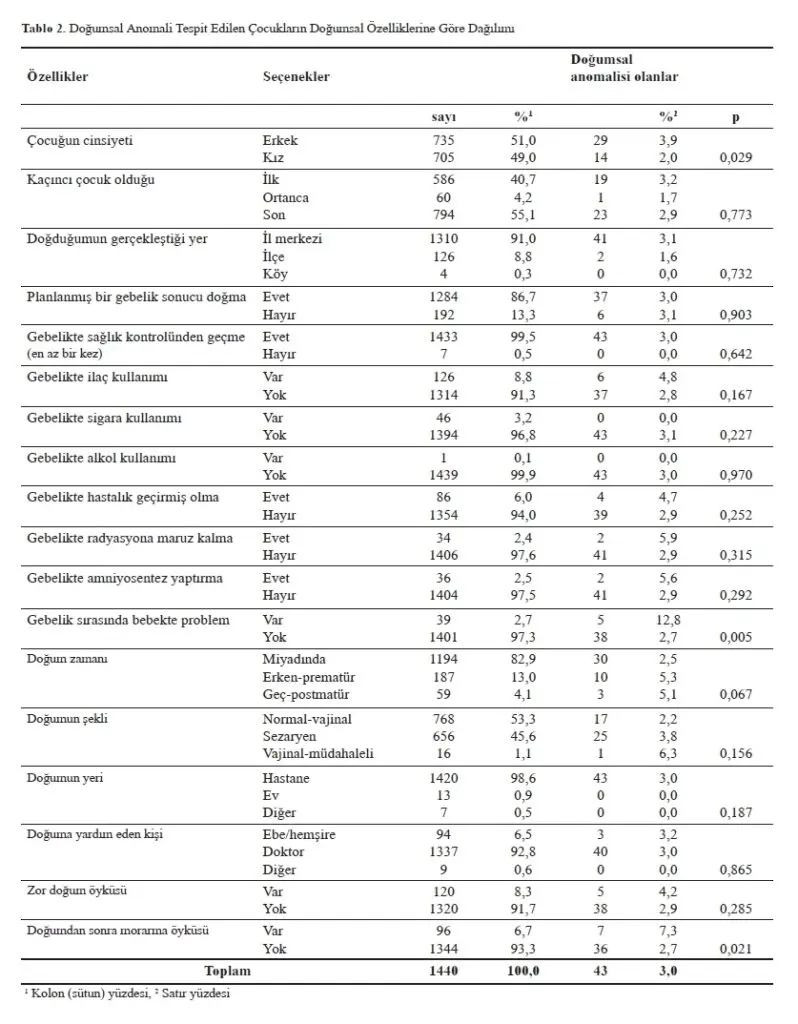

The distribution of children with congenital anomalies according to their congenital characteristics is shown in Table 2. The average age of the research group was 33.5±17.5 months. 51.0 percent were male, 55.1% were the last child, 86.7% were born as a result of a planned pregnancy, 82.9% were born at term, and 53.3% were born normally vaginally. 98.6 percent of them were born in the hospital and 92.8 percent of them were given birth with the help of a doctor. 8.3 percent had a history of difficult birth and 6.7% had a history of postpartum bruising. The cases of children in the research group having congenital anomalies are shown in Table 3. It was determined that 2.9% of the research group had a congenital anomaly. The five most commonly detected anomalies are (in order); undescended testicles (0.6%), other congenital malformations of the male genital organs (0.4%), congenital malformations of the heart chambers and connections (0.2%), other congenital malformations of the digestive system (0.2%) and congenital deformities of the hip (0.03%).

The frequency of congenital anomalies is in boys (3.9%), among children whose mothers are retired (11.5%), among those who are told that the baby has a problem during pregnancy checks (12.8%), and among those with a history of bruising after birth (7.3%). was significantly higher than the others (p<0.05, p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.05, respectively). The incidence of congenital anomalies did not differ between groups according to other independent variables of the study.

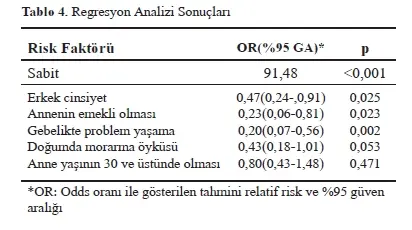

For multivariate analysis, variables determined to be associated with anomaly in univariate analyzes (gender[being male], mother’s retirement status, reported problems during pregnancy, history of bruising at birth) and maternal age reported to be associated with anomaly in the literature (significant difference in univariate analyses). When taken into the regression model, male gender, the mother’s retirement, having problems during pregnancy were determined as variables associated with the occurrence of an anomaly. History of bruising and maternal age were not identified as risk factors (Table 4).

ARGUMENT

At the end of this study, which was conducted to determine the frequency of congenital anomalies and affecting factors in rural Isparta, the frequency of congenital anomalies detected in the research group was determined as 3.0%. It is reported that major congenital anomalies occur in 2-3% of live-born babies (8). Although the frequency of congenital anomalies detected in this study was determined only by applying a survey and physical examination and detailed and advanced examinations were not used, it is compatible with the literature. In a study conducted in Van in our country (9), the frequency of congenital anomalies was reported as 1.12%, and in the study conducted by Bayhan et al. (10) in Dicle, it was reported as 2.79%. Although the frequency of congenital anomalies detected in this study is not much different from the figures in the literature, it is slightly higher than the studies conducted in other provinces of our country. It is reported that the most common congenital anomalies in our country and in the world are cardiac malformations and neural tube defects (11, 12). In the study conducted in Van (9), it was reported that congenital anomalies were most frequently seen in the central nervous system, gastrointestinal system and urinary system, respectively. In the study conducted by Bayhan et al. in Dicle (10), the most frequently involved system was reported to be the central nervous system. The most common type of congenital anomaly detected in this study was undescended testicle. This is followed by other congenital malformations of the male genital organs and congenital malformations of the heart chambers and connections. In the International Classification of Diseases and Health-Related Problems, the two most frequently observed anomalies in the research are in the group of congenital malformations of genital organs. Accordingly, the second most common condition is congenital malformations of the circulatory system. In this study, it is a difference that congenital malformations of the genital organs were identified as the most common malformation in rural Isparta. More comprehensive studies questioning the factors that may reveal this situation should be planned in the future. Genetic and environmental factors affecting the frequency of congenital anomalies in a society are specific to that society.

The factors that play an important role in the emergence of congenital anomalies in our country are examined in several groups, as mentioned in the introduction section, and these factors are listed as the main reasons in our country, where consanguineous marriages are common, births begin at an early age and continue until advanced ages, and antenatal care remains below the targeted level (13). ). Consanguineous marriage is one of the important situations affecting the epidemiology of genetic diseases and is preferred by 20%, perhaps more, of the world population. At least 8.4% of the children born are born from consanguineous marriages. It is especially common in the Western Mediterranean and Southern India. It has been reported that the risk of having a disabled child in the consanguineous population will double compared to other populations and the incidence will be around 8% (14). In this study, the frequency of consanguineous marriage was determined as 11.7%. Although this study was conducted in rural areas, it was determined that consanguineous marriages were at a lower level than the 29.2% reported frequency of consanguineous marriages in Turkey (15). In a previous study conducted in the same region (6), the frequency of consanguineous marriage was determined as 12.9%. It has been determined that the rate of consanguineous marriages is different in different regions and regions of our country. It was observed that it was lowest in the Aegean and Marmara regions, and gradually increased in the Black Sea, Central Anatolia, Mediterranean, Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia Regions. While this level is 12.8% in the Aegean Region, it increases to 34.9% in the Southeastern Anatolia Region (16.17). In recent years, the prevalence of consanguineous marriages has been decreasing in our country. Public education about consanguineous marriage and its relationship with genetic diseases has an impact on this change. Individuals stay away from consanguineous marriages to avoid genetic diseases that may occur with consanguineous marriages. In studies conducted in different regions of our country on consanguineous marriage and its effects, evidence has been obtained that consanguineous marriage increases prenatal and postnatal mortality, spontaneous abortion, congenital anomalies and sterility (16,17). In this study, when the relationship between consanguineous marriage, which was reported as an important risk factor for congenital anomalies, and the distribution of congenital anomalies was examined, the frequency of congenital anomalies did not differ according to consanguineous marriage. Variables determined to be associated with congenital anomalies are the working status of the mother, problems detected in the baby during pregnancy checks, and a history of bruising after birth. More congenital anomalies have been detected in the children of retired mothers. At first glance, this may seem to be due to the mother’s age rather than her working status; the relationship between maternal age and malformations is reported in the literature (9). However, this condition determined in this study is not the one that reveals the congenital anomaly, On the contrary, it has been interpreted as a condition that occurs due to having a child with a congenital anomaly. The regression analysis supports this interpretation. It has been determined that congenital anomalies are more common in those whose babies are found to have problems during the checks. This result is also expected. It occurred as a result of the family choosing to give birth to the baby even though they knew there was a problem with the baby. Congenital anomalies were detected more frequently in those with a history of postnatal bruising. It is also expected that babies with anomalies may experience respiratory distress. In this study, the frequency of congenital anomalies was found to be significantly higher in boys than in girls. In the study conducted in Van (9), no difference between genders was detected in terms of congenital anomalies. In a study conducted in Kayseri (18), it was reported that congenital anomalies were responsible for 25.5% of the deaths in girls and 32.3% of the deaths in boys, but there was no difference between genders. In fact, the birth risks of boys are high due to their gender, and especially urogenital system anomalies are more common in male babies (18). The most frequently identified congenital anomaly in this study was undescended testicle, and it was thought to be the main reason why the frequency of congenital anomalies was found to be higher in boys than in girls.

In this study, the age of mothers of children with congenital anomalies was not found to be different from others. In the study in Van (9), it was reported that young mothers gave birth to malformed babies more frequently, and it was commented that this situation may be related to the fertility structure specific to the region.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In this study, it was determined that the frequency of congenital anomalies in children under five years of age in rural Isparta was consistent with the literature. It has been determined that congenital anomalies are more common in boys than in girls, in children with problems in pregnancy control and in those with a history of bruising at birth. The most common anomaly is undescended testicle.

Genetic and environmental factors affecting the frequency of congenital anomalies in a society are specific to that society. The factors that play an important role in the emergence of congenital anomalies in our country are examined in several groups, as mentioned in the introduction section, and these factors are listed as the main reasons in our country, where consanguineous marriages are common, births begin at an early age and continue until advanced ages, and antenatal care remains below the targeted level (13). ).

The approach to preventing congenital anomalies is a multifaceted approach. Reducing consanguineous marriages, preventing advanced age pregnancies, providing screening for anomalies in the antenatal period to every pregnant woman, and informing the society about genetic and environmental factors that may affect the baby while in the womb are important steps of this approach. Developing a registry system that will monitor congenital anomalies in our country will allow the identification of common anomalies and diseases, the recognition of factors that may cause them and the development of precautions (13). It is also important for families with children affected by congenital anomalies to be identified and directed to centers where they can receive health care. Similar studies should be expanded to other regions to reveal regional characteristics.

resources

- Kalter H. Teratology in the 20th century: environmental causes of congenital malformations in humans and how they were established, Neurotoxicol Teratol 2003; (25): 131-282.

- Atasü T, Öçer F(eds). Factors Harmful to the Fetus and Newborn During Pregnancy Istanbul: Nobel Medicine Bookstores; 2000.

- Moore KL, Persaud TV. Congenital anatomical anomalies or human birth defects. In: The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology, 8th ed, Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2000; p. 457-487.

- Mollahaliloğlu S, Hülür Ü, Yardim N, Özbay H, Çaylan AK, Ünüvar N, Aydın S (eds). Outlook on Health in Turkey 2007; TR Ministry of Health and Refik Saydam Hygiene Center Presidency 2007; Ankara.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Control of Hereditary Diseases, Technical Report Series 865 1996; WHO, Geneva.

- Uskun E. Disability Epidemiology in Isparta Province, Isparta: Süleyman Demirel University; 2002.

- World Health Organization (WHO). The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 2011; WHO, Geneva.

- Barrow MV. A brief history of teratology to the early 20th century, Teratology 1971; (4): 119-130.

- Kurdoğlu M, Kurdoğlu Z, Küçükaydın Z, Kolusarı A, Adalı E, Yıldızhan R, Şahin HG, Kamacı M. Incidence and distribution of congenital malformations in the Van region, Van Medical Journal 2009; (16): 95-98.

- Bayhan G, Yalınkaya A, Yalınkaya Ö, Gül T, Yayla M, Erden AC. Frequency of congenital anomalies in Dicle University Faculty of Medicine, Perinatology Journal 2000; (8): 99–103.

- Loane M, Dolk H, Kelly A, Teljeur C, Greenlees R, Densem J, and A Eurocat Working Group, Paper 4: EUROCAT statistical monitoring: identification and investigation of ten year trends of congenital anomalies in Europe, Birth Defects Res A 2011; (91): 31-43.

- Öztarhan K, Gedikbaşı A, Yıldırım D. Prevalence and distribution of congenital abnormalities in Turkey: differences between the prenatal and postnatal periods.Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2010; (50): 221-225.

- Ütine GE, Boduroğlu K. Protection from congenital anomalies, Journal of Child Health and Diseases 2013; (56): 28-37.

- Uskun E. Consanguineous marriages. Journal of Continuing Medical Education 2001; (10): 54-56.

- Timur S. Family Structure in Turkey, Hacettepe University Publications 1972, Ankara.

- Sümer H, Koçoğlu G, Polat HH, Koçoğlu F. Frequency of consanguineous marriage in Sivas city center and villages and its effects on maternal and child health, Journal of Cumhuriyet University Faculty of Medicine 1990; (18): 291 – 294.

- Akın G. Consanguineous Marriage in Denizli Rural Area and Factors Affecting It, Journal of Ankara University Faculty of Languages, History and Geography, 2000; (3): 67-80.

- Balcı E, Küçük E, Gün İ, Gülgün M, Kılıç B, Çetinkara K. Infant deaths in Melikgazi district of Kayseri province in 2006, Fırat University Health Sciences Medical Journal 2008; (22): 323-326.